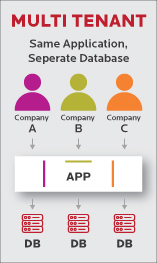

Multi-Tenant – This means that all customers of a vendor application share the same code base. So, in a data center, multiple clients (Tenants) can each have their own unique company data, but they share the same application program. Their data is separated and protected by sophisticated firewalls, so they never touch each other. And when there is a release of functionality, it is deployed to all data centers around the world, essentially available to every customer on nearly the same day.

Company Data – The Application vendor that supplies the software and is typically the host of company's data as well.

Interface – The interface is exclusively through a Web OS on a desktop or a mobile device. There is no proprietary desktop app required. For Web users, this makes the application a bit more user-friendly, since a desktop/laptop browser is used for most business Cloud applications, and the mobile interface (which will require an App download) comes standard with the subscription.

How You Pay – Cloud applications are delivered as a subscription, typically with a multi-year contract and annual payments. Legacy apps are purchased one time and then you pay an annual maintenance fee. Cloud applications have maintenance fees as well, but that fee also includes the hosting and infrastructure. In this way, as with the multi-tenant software, the cost of the software updates, support and the hardware infrastructure or hosting fee is included with a single periodic payment.

Configurable vs Customizable – Typically, the underlying programing is NOT exposed in Cloud Software. And depending on the product, configurability without the need to know a programming language is considerable. There is enough flexibility from customer to customer to configure the application to meet the requirements of each individual company…without programming.

The Economic Beauty of Standards

The pure commonality of the platform and the regular release of version updates, several times a year, provides an incentive to do things differently from legacy on-premise systems. Over time, as a product gains market momentum and builds a community of users, Leading Practices begin to emerge. (some say Best Practice, but I have always believed that Best is contextually incorrect. Who's to say what is Best?). The more popular Leading Practices built upon community consensus will eventually be incorporated into the product upgrades.

In essence, the product becomes a work of art and innovation from a collaboration between the vendor and its community of users. This results in a better solution that is almost obsolescent proof, always being updated for the latest industry demands. The benefit is a much more efficient and cost-effective way of processing data.

The Rapid Deployment Solution (RDS)

How many times have you heard the term "out-of-the-box" when describing how Companies want to implement Cloud applications? Because leading practices are so widely accepted, this is almost a reality, but it never will be 100% true. Every company and user want something a little different. Without accommodating user needs, innovation would stop. Vendors need that feedback to keep their product current and relevant.

Loosely defined (meaning it's my definition), an RDS is an implementation approach that:

- leverages leading practices built into a pre-configured instance of the application

- can be quickly deployed to a customer

- meets from 50% to 80% of the customer's functional requirements before requirement adjustments

"Companies spend 2 to 4 times the effort and cost to try to make the system a final product that's acceptable. Then, a month after Go-Live, they start changing it!"

The RDS avoids the "What-do-you-want?" approach in favor of a "Why-won't-this-work?" approach. When I explain this to customers, I always get the same question, "Well, what if it does not meet our requirements?" After almost 17 years of implementing in the traditional method (meaning non-RDS), what I have experienced is irony.

Companies that take the traditional approach will spend 2 to 4 times the effort and cost to try to make the system a final product that is acceptable to all their employees. Then, about a month after Go-Live, they start changing it.

The RDS was not intended to be perfect, but rather fast to implement and reasonably acceptable, (the 80/20 rule of software). This comes with the understanding that, after the go live, the company will spend the effort over time to refine the system based on business feedback.

"Bottomline, I am a strong proponent of RDS, except for one thing, the RDS approach almost never works well without one very important factor: a "Stabilization Strategy!"

The Downside of RDS

The greatest aspect of the RDS is that you have a viable system, implemented in record time in less than half of the typical duration and for as little as 20% of the price of the full requirements approach. That is compelling, especially when you can have a great product and save hundreds of thousands of dollars in the process.

So, what's wrong with the RDS approach?

Readiness! The RDS is a great "technical" solution. It works. However, these enterprise systems are complex and powerful and there is a tremendous amount to know and learn about its operation. Just like learning to drive a car or fly a plane in a simulator, they help but are no replacement for the real thing. It takes time to develop a tacit understanding of the system.

While the RDS can be implemented quickly, when it's time to go-live and handover the keys to the system to the customer, there has almost never been enough time for the customer's system administrators to really learn to drive the system. Because of not being ready, frustration and stress often ensues for which the system will likely get unfairly blamed. You need time to fly the plane with an expert nearby, ready to take over. Only after many hours do you get to fly solo.